School of Business Professor Uses Expertise in Teamwork To Help NASA Prepare ‘Resilient Astronauts’ to Travel to Mars

Management Professor John Mathieu, an expert in team dynamics, is helping NASA figure out the complexities of developing a socially compatible and resilient crew of astronauts to travel to Mars.

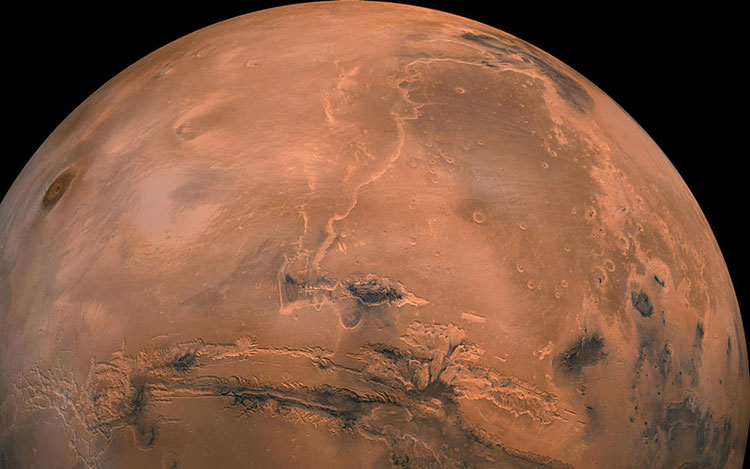

Consider the challenges: an international crew of up to six astronauts will contend with isolation from their families, cramped living quarters, and extensive boredom that is punctuated with life-threatening danger.

They will sleep, dine and work side-by-side with their colleagues for up to two years, and privacy will be minimal. To send a simple message to mission command, and receive a response, will take 45 minutes, thus requiring the crew to be largely autonomous.

When first commissioned by NASA to do this research three years ago, Mathieu and two colleagues focused on members’ attributes that would form a compatible team. However, because astronauts from multiple countries will be involved in a journey to Mars, when and if the trip occurs, the opportunity to select candidates based on specific attributes seemed unlikely.

“Instead, the project developed into keeping a team ‘psychologically healthy.’ Our goal is to develop resilient, adaptive and self-sustaining teams for long-duration space exploration,” Mathieu said. “How can we strengthen the teams we work with and build team resilience? How can those astronauts withstand and overcome the challenges they will face?”

Although the focus of Mathieu’s research is on space travel, it has many implications for high-stress situations on Earth, including the formation of highly efficient surgical teams and air-travel teams, including pilots and air-traffic controllers.

For example, Mathieu and colleagues worked with a large teaching hospital in Colorado which had issues with operating room teams. A retired orthopedic surgeon came in to coach them in team-improvement techniques. Half of the 40 surgeons went through a training program that addressed everything from mutual respect, check-backs, cross monitoring, conflict resolution and process planning. They discussed each procedure’s success and what could be improved.

Medical observers watched 223 procedures before and after the coaching, and found that the communication training significantly reduced errors and led to efficiencies, including reduced distraction, fewer delays and shortened surgery times. “A simple thing like introducing yourself to those you don’t know on the team can create a more cooperative, friendly tone,” Mathieu said.

“In most work situations, teams tend to avoid ‘hot button’ issues and stay within a safe zone,” Mathieu noted. “Teams are often not good at resolving conflicts because members are afraid if they address a conflict, it’s going to be explosive.”

Yet, in space, as in other life-and-death circumstances, the ability to work together is vital. In fact, techniques to improve communication and resolve differences have demonstrated up to a 25 percent improvement in team effectiveness, Mathieu said. Considering that 70 to 80 percent of aviation mishaps are the result of teamwork problems, that’s significant. Likewise, some 70 to 75 percent of surgical errors also are the result of miscommunication among medical teammates, he said.

“These are huge issues that really matter in everyday life,” said Mathieu, whose research partners included Scott Tannenbaum, president of The Group for Organizational Effectiveness and Professor Eduardo Salas of the University of Central Florida.

One solution that they came up with is a communication and debriefing “tool,” that allows participants to reflect on a work experience, provide a “safe” environment for discussion and focus on team processes. Input from all participants is used, issues are discussed, and an action plan is put into place. Best of all, the debriefing communication can be implemented by the astronauts without additional assistance.

How do they know if the debriefing tool will work in outer space? Mathieu and his colleagues have conducted three increasingly challenging experiments, funded by NASA, to demonstrate it. Setting up life-like scenarios, they staged frustrating and challenging experiences that astronauts might experience in space.

In the first experiment, they had students communicate in a lab study while simulating delays and other issues similar to what would happen during space travel to Mars.

In the second phase, they put several four-member crews of scientists in the Human Exploration Research Analog (HERA) for a week at a time and had them perform tasks similar to those that astronauts perform in space. One of the issues they found in the experiment was that scientists were complaining about not getting beneficial sleep. Using the debriefing process, they were able to discuss what was hindering sleep, what would be helpful and what can be done.

The third, and most intense, study was conducted with astronauts slated to work on the international space station, who were training in an underwater craft, called NEEMO. NEEMO is almost a cross between a submarine and a spacecraft and astronauts conduct numerous “space walks” under water. It provided a full-blown test of feasibility and realism.

“In all three environments, the participants liked the debriefing/communication tool and felt it solved the problems,” Mathieu said. “The debriefings had a big impact on their performance. Team resilience and performance increased significantly over time.”

This communication/debriefing tool demonstrated effectiveness consistently, Mathieu said. Generally speaking, teams that use the debriefing tool show around a 20 percent increase in performance, less frustration and are better ability to work together.

Although Mathieu and his colleagues are pleased with the results, they continue to explore evolving research in the relatively new field of team dynamics, in hopes of making every team—from college basketball to a landscaping crew to astronauts—work more effectively. On the horizon are better ways to measure interpersonal dynamics, more sophisticated analytics, customized interventions, and multi-team performance systems, he said.

“Who knows if we’ll ever go to Mars,” Mathieu said, “but if so, our astronauts will face challenges unlike those we’ve ever seen before.”